Landscape Constructed and Wild

Juried by Alexxa Gotthardt

Curatorial Statement

Between 1899 and 1901, Claude Monet developed a preoccupation with fog (the word “smog” had not yet emerged in the English language). On frequent visits to London, he’d observe its thick vapors—ethereal condensation mingled with industrial pollutants—as it descended on the city, shrouding the Thames and Charing Cross Bridge. Light, color, and objects transfigured through this hazy prism: “The fog in London assumes all sorts of colors,” he told an interviewer in 1901. “There are black, brown, yellow, green and purple fogs, and the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs.” For Monet, fog became fodder for paintings that captured the provocative, intoxicating interaction between the natural world (in this case, river and sky), the built environment (bridges), and human perception (awe).

Of course, the relationship between landscape and human intervention has long fascinated artists, stretching back to ancient Greece and Rome, where painters applied frescoes depicting lush landscapes, ambrosial gardens, and vast celestial sweeps to the walls of homes. As our surroundings have shape-shifted through the ages, so too have artistic motivations and mediums. But the mediation between wild and constructed landscapes remains a powerful tool to reflect on our contemporary condition. As landscapes slip, smolder, decay, and reconstitute around us, shaping our present and futures, the work assembled here frames—and gives mesmerizing form to—their precarity.

In 2005, Monet’s fog paintings became the subject of a paper by English climatologist John E. Thornes. In it, Thornes proposed that air pollution levels in early-20th century London could be deduced by comparing the haziness depicted in Monet’s Charing Cross Bridge canvases to the 1901 London Fog Inquiry. It’s a suggestion that reanimates Monet’s fascination with landscape and the swirling atmospheres that give it meaning: ‘‘A landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment; but the surrounding atmosphere brings it to life, the air and the light, which vary continually. For me, it is only the surrounding atmosphere that gives subjects their true value.’’

– Alexxa Gotthardt

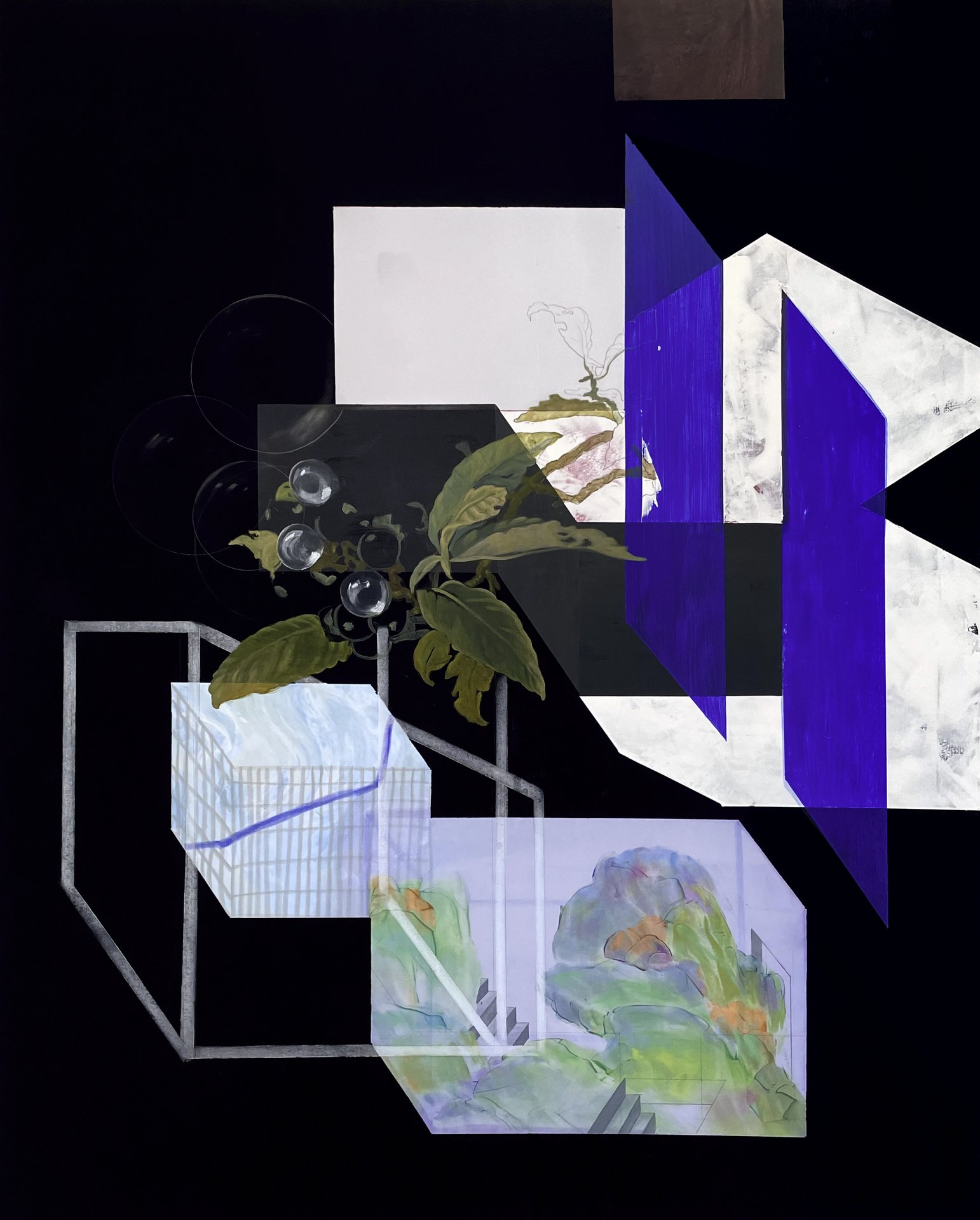

Room 1

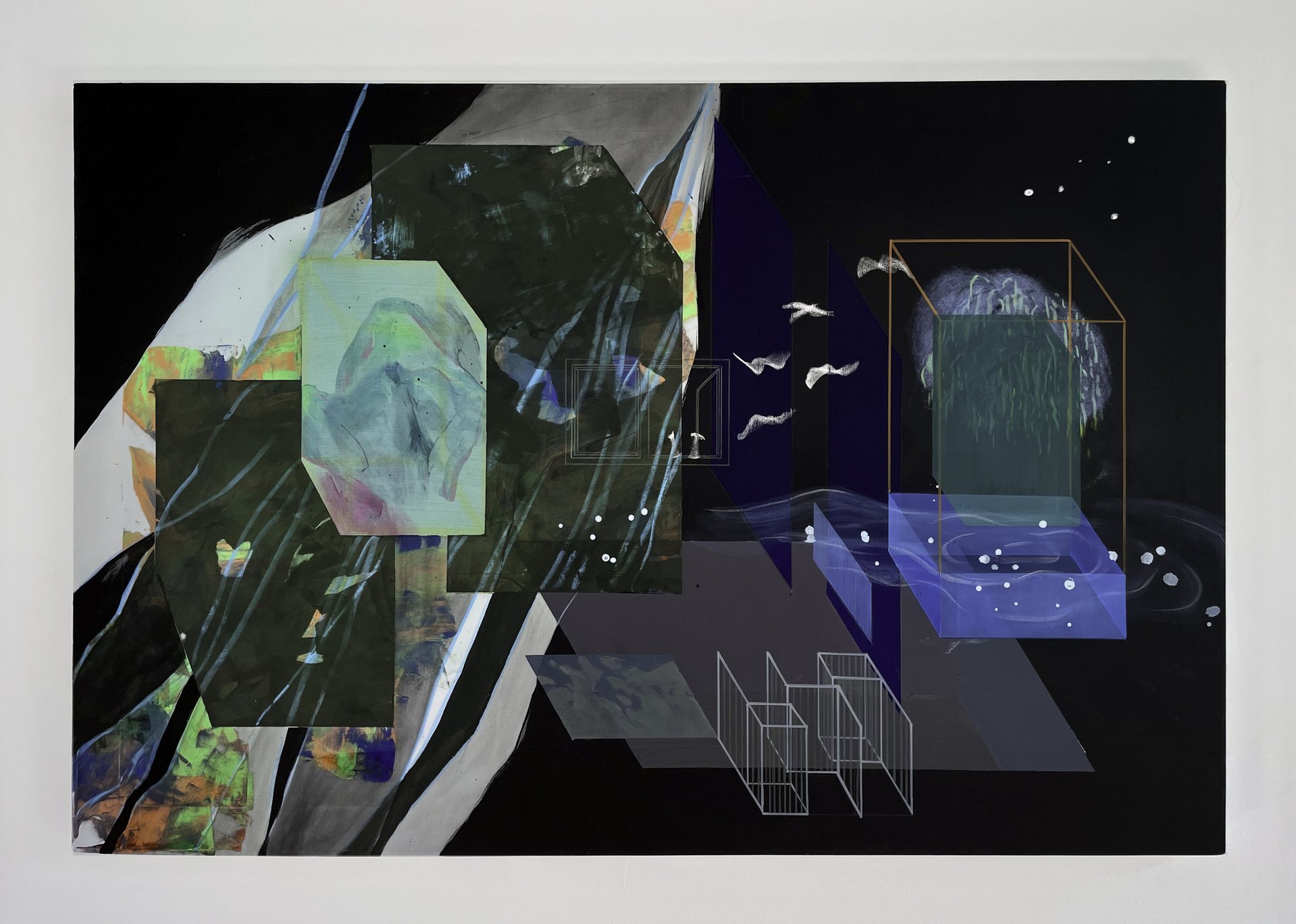

Working across mediums, these six artists use blurring, layering, and close-looking to abstract landscapes and foreground the auras and emotions they produce.

Featured Artists: Weina Li, Shona Macdonald, Michelle Mackey, Julia Paul, Matt Roberts, and Emily Wallerstein

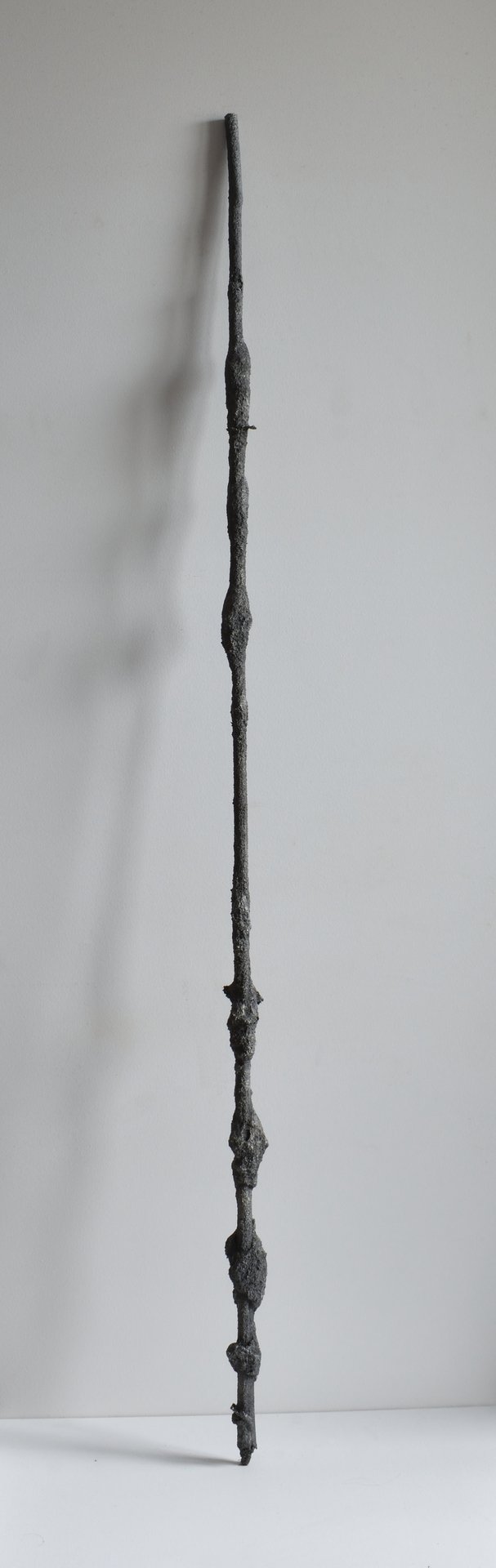

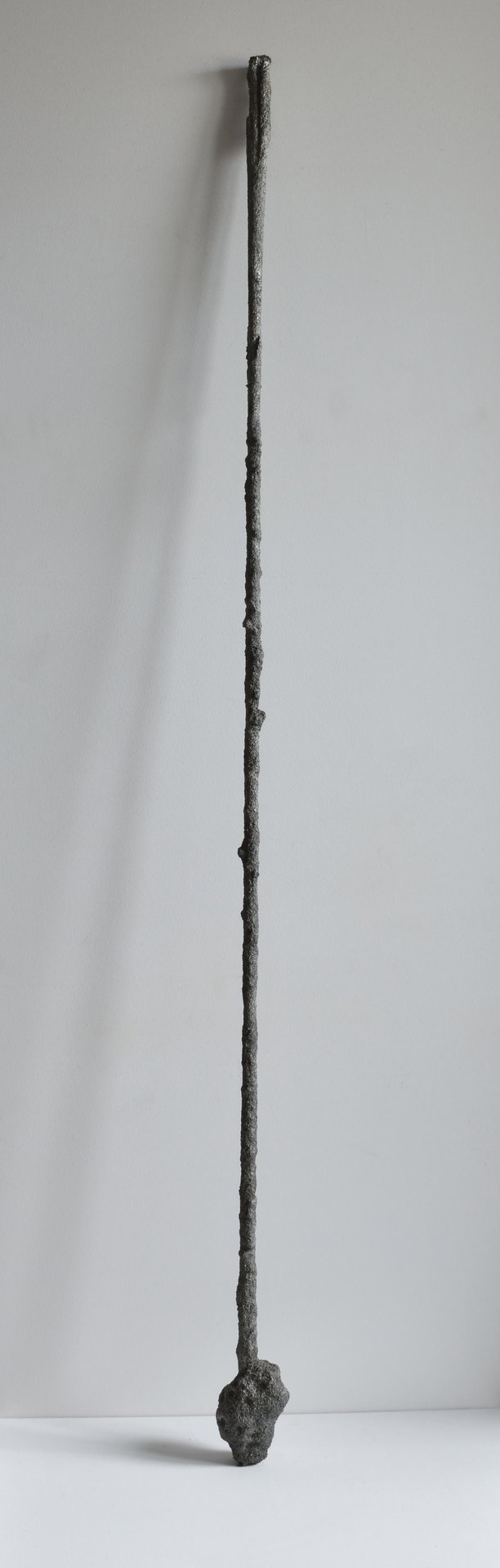

Room 2

Allusions to topography and geology inspire deeper meditations on excavation and extraction in the works of Austin Irving, Zara Kuredjian, Lauren Skelly Bailey, Ernie Wood, and Eric Ziegler.

Featured Artists: Austin Irving, Zara Kuredjian, Lauren Skelly Bailey, Ernie Wood, and Eric Ziegler

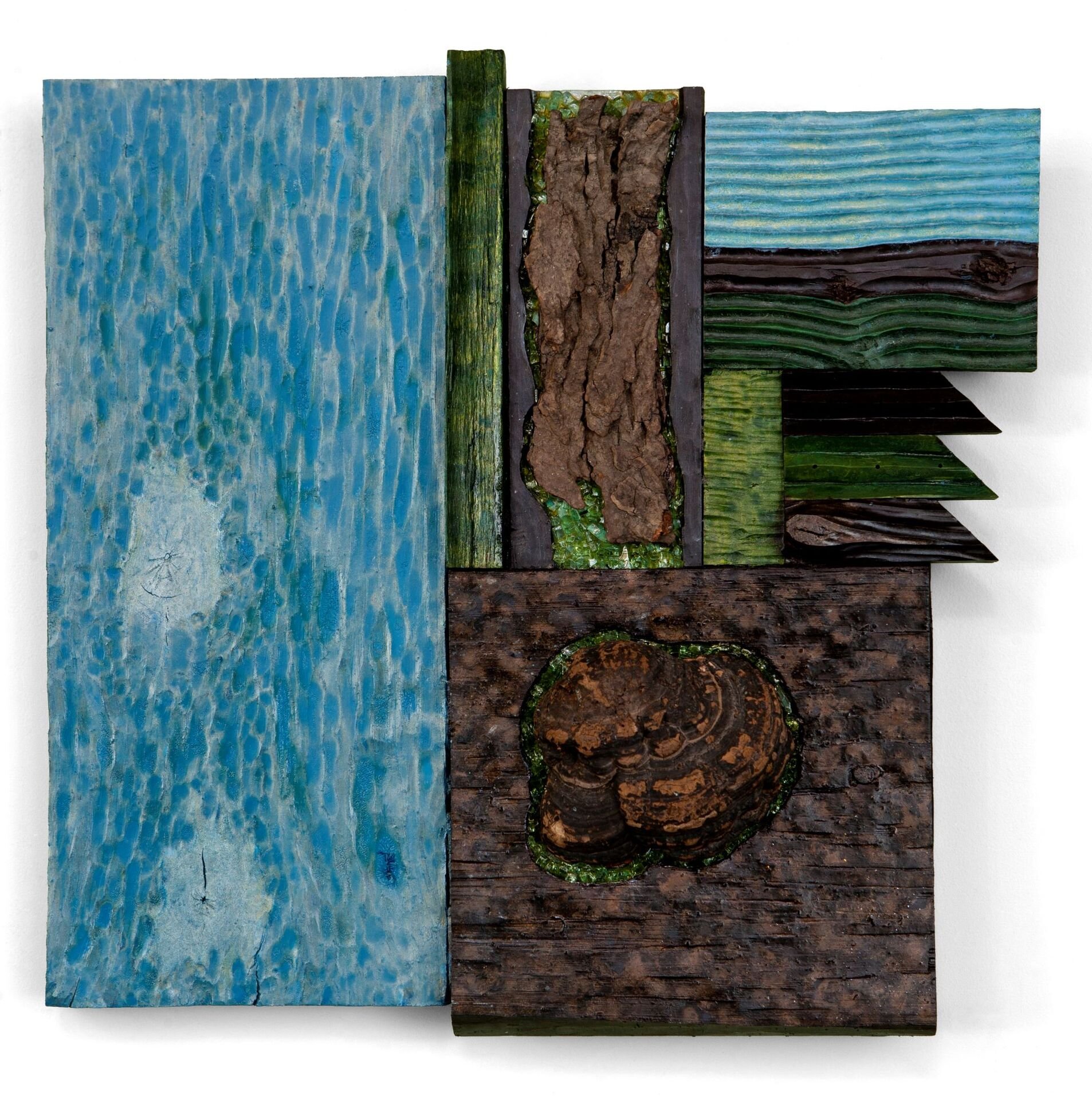

Room 3

Here, robust materiality and physical processes of stacking, accumulating, deconstructing, and reconstructing explore landscapes in flux. In some works, found and discarded materials are reconstituted to create new, robust topographies.

Featured Artists: Barry Beach, Marie-Dolma Chophel, K. Daphnae Koop, Pia Larsen, Docey Lewis, and Benoit Maubrey

Room 4

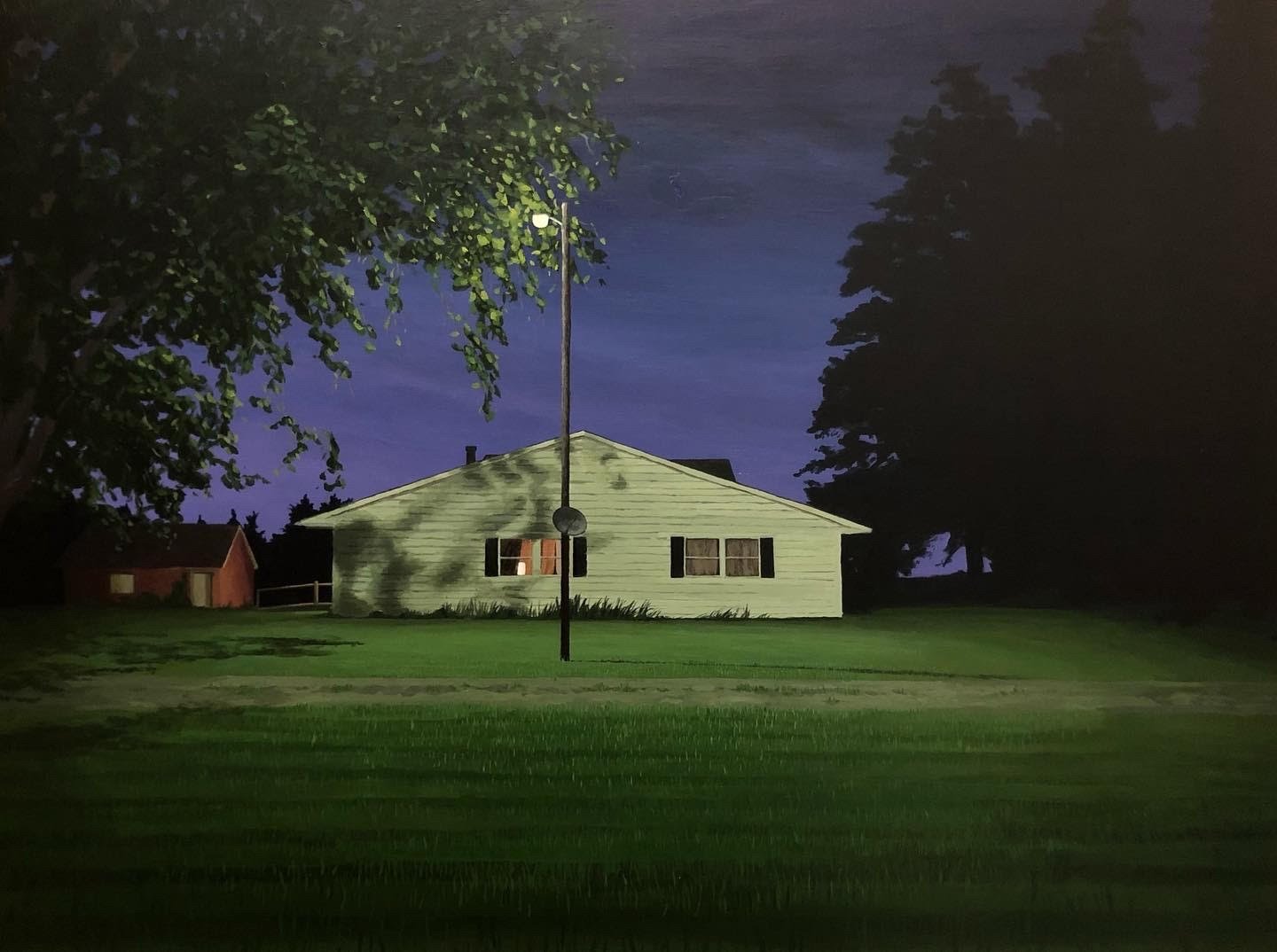

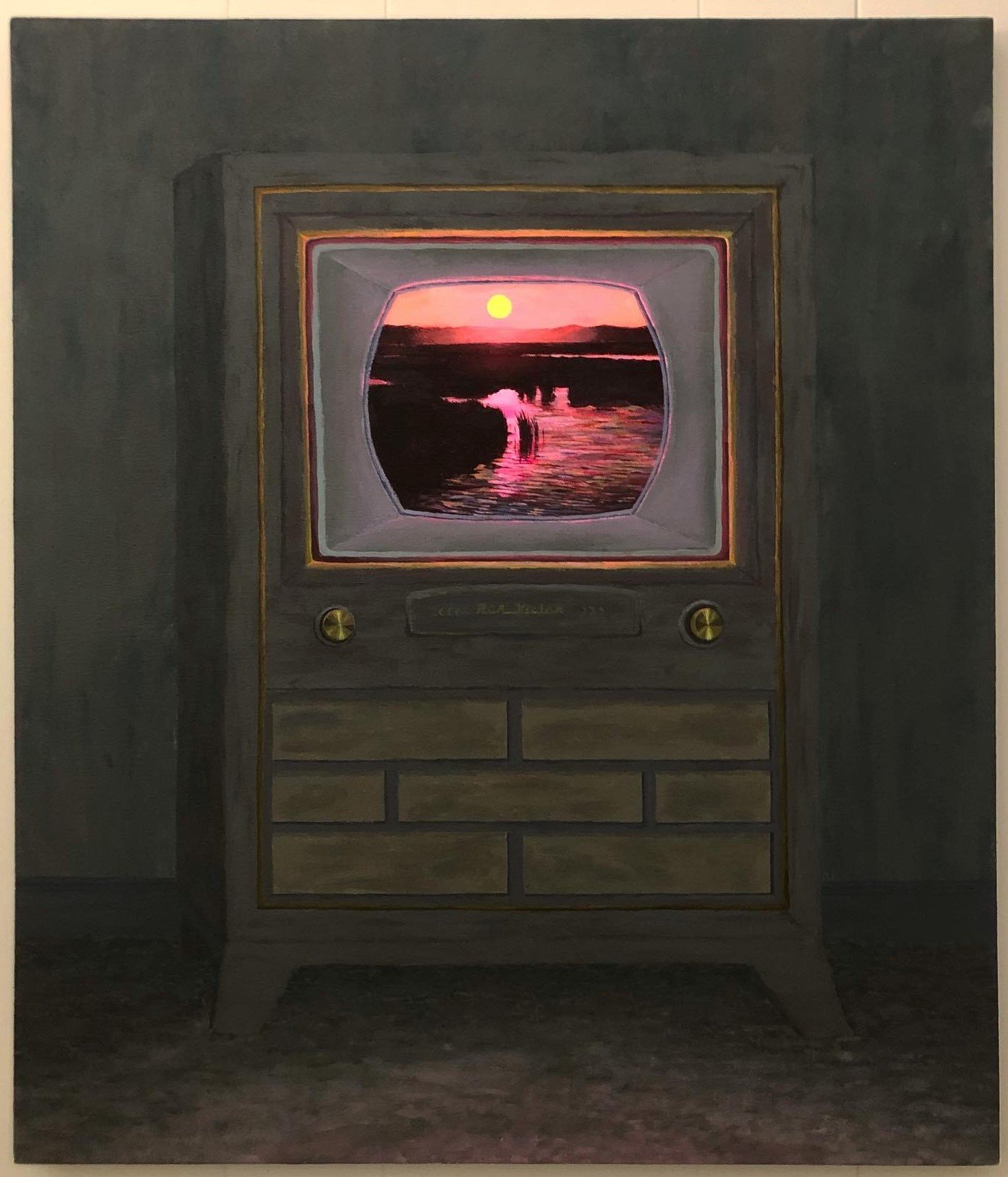

Investigations of memory, home, and identity power the environments depicted by Cassandra Chalfant, Ye Cheng, Farima Fooladi, and Domingo Nuno. These hybrid, layered landscapes radiate with personal associations—from displacement and longing to safety and tenderness.

Featured Artists: Cassandra Chalfant, Ye Cheng, Farima Fooladi, and Domingo Nuno

Room 5

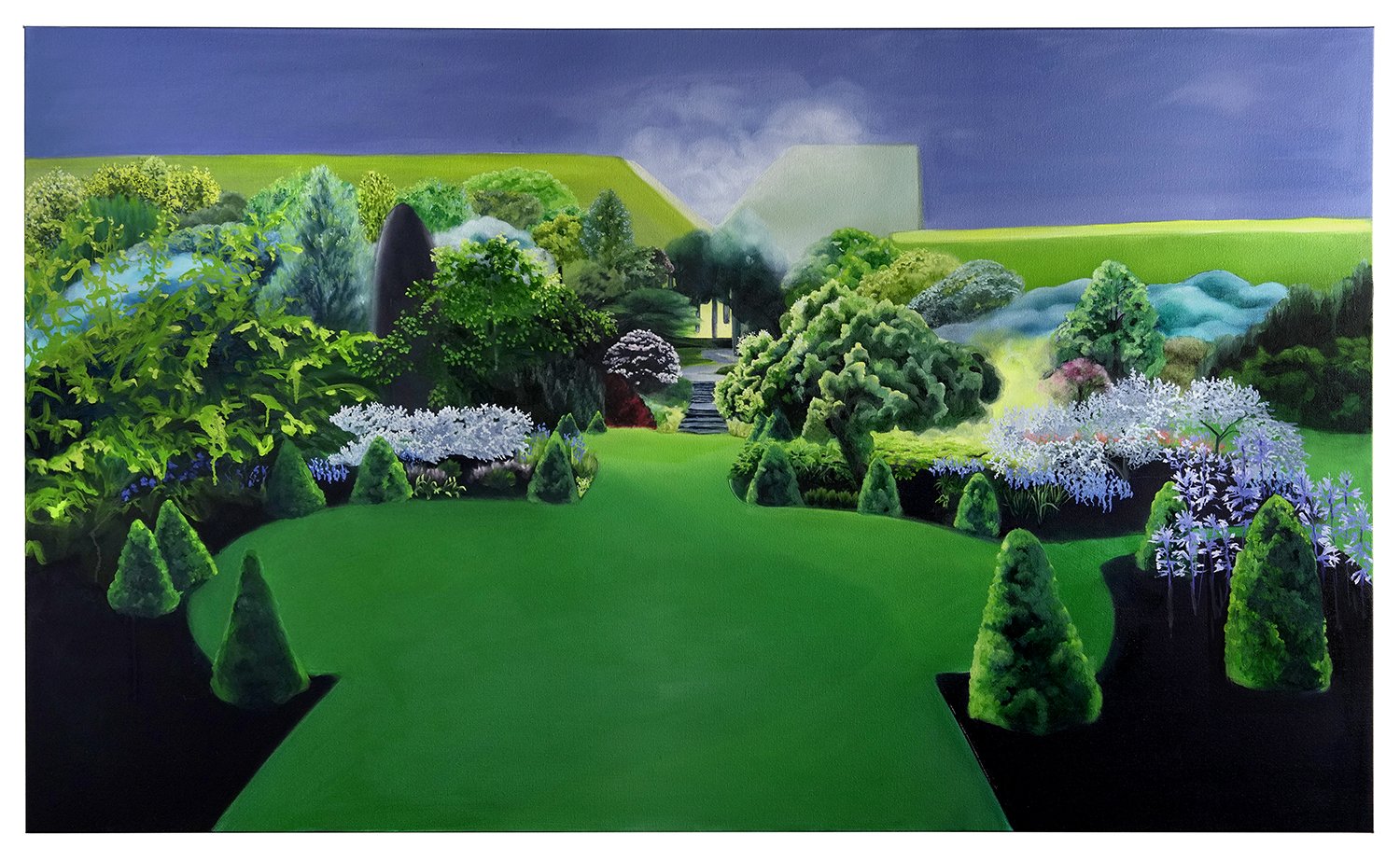

Fantasies and futures inform works by Deena Capparelli, Victoria Crayhon, Jessica Ecker, Claire Hansen, and Hui Tian. Whether capturing climate change preparations that imply a grim fate, as in Crayhon’s photographs, or concocting otherworldly Edens, as in Hansen’s digital collages or Capparelli’s paintings, these landscapes explore a powerful mix of adaptation and escapism.

Featured Artists: Deena Capparelli, Victoria Crayhon, Jessica Ecker, Claire Hansen, and Hui Tian