Shape Show

Juried by Andrew Gardner

Curatorial Statement

“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way... things I had no words for.”

― Georgia O'Keeffe

Visual clarity is not something that babies achieve until nearly the first year of life. Newborns initially experience the world as a contrast between light and dark, which together delineate the visible world into a series of interrelated shapes. Large shapes, small shapes, human shapes, pet shapes, flower shapes, car shapes, tree shapes, street shapes—shapes of all kinds dominate the first visual experience of humans’ interface with the world. Before speaking, before full vision itself, there is shape.

The cave paintings at Lascaux—among the oldest known artworks in existence—are not perfect depictions of the observable world. Rather, they are representations of reality, a language of shape. We understand that these are galloping horses because there is universal agreement about the shape of a horse. Think of the standardized systems of shape that govern our modern understandings of the world: written languages the world over, which are themselves a series of agreed upon shapes; the signage system chartered by the UN that governs the shapes of road signs; or the five basic shapes in the VSEPR model of organic chemistry that inform the basic structure of an atom. Shapes are the basis of visual systems the world over, from how we know about the world, move through it, or the literal substance of it.

Representing that which can be seen through the human eye dominated much of Western art until the advent of the reproducible image in the 19th century, when artists sought to turn away from literal representation and towards a language about pure form. The Impressionists sought to create impressions of a world through stroke and line—if you knew the shape of a body or a mountain, what did it matter if it didn’t look exactly like the real thing? In the 20th century, the Cubists sought to break the visible world down to its constituent shapes, turning human forms into geometries that alluded to reality, but only just so. In the 21st century, where the ecosystem of imagery churns through our screens on a near constant basis, artists continue to employ the visual acuity human beings develop for shape from our earliest years. Shapes, it turns out, are both pleasing to the eye and a powerful rejoinder to the frenetic consumption of reality that we are force fed daily.

With this in mind, the Shape Show presents works by artists who employ shape to various ends, whether through non-representational abstractions or with perspectives of the visible world rendered in unexpectedly shapely ways. Together, these artists create a language of shape that is at once personal and universal, works that harken back to our earliest understandings about the visible world and the role that shape plays within it. – Andrew Gardner

Grid and Line

James Eli Bowden / Anna Moore Kaplan / Bill ODonnell / David Brown / Greg Chann / Robert Klewitz / Shannon Guzzo / Alberto Mena / Elly Dec / Cathy Bruegger

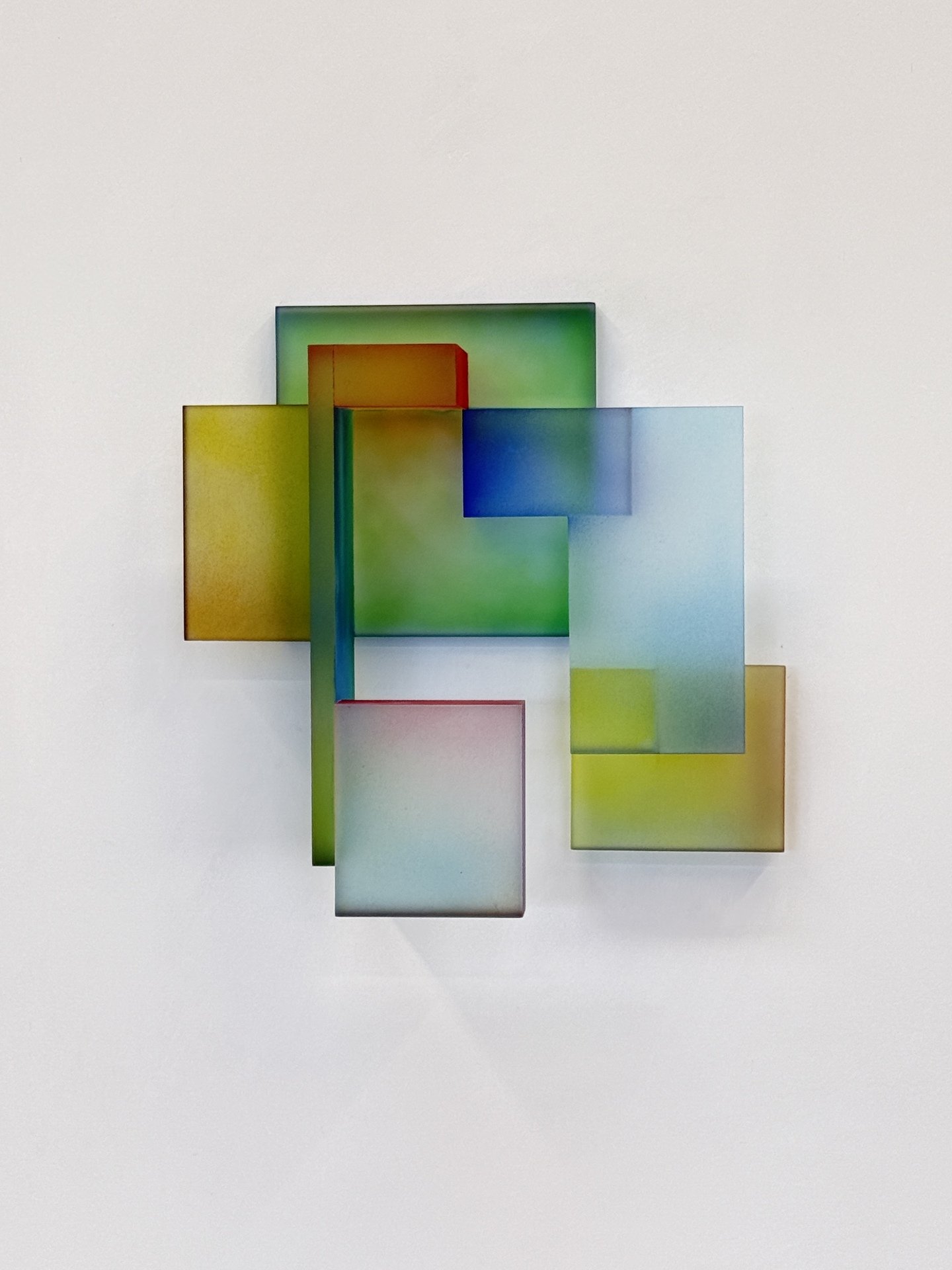

The man-made world is full of rectilinear shapes, where right angles and straight lines are the domain of engineers, architects, and builders. Grids and lines are also ripe terrain for artists, too—as Paul Klee, a leading Bauhaus artist famously quipped, “A line is a dot that went for a walk.” The artists presented in this section draw these lines together to create sumptuous geometries, rendering a vision of pure shape that revels in the pleasing allure of rectilinearity.

Behind the Curve

Christine Barney / Emily Bartolonee / Geneva Bergelt / Karen Birnholz / Chuck Fischer / Dan Woodard / Ashoke Chhabra / Danielle Gottesman / Meryl Blinder

At a molecular level, a circle is among the most basic shapes. Within the circular system of our galaxy, the spherical planetary orbs and moons are in rounded formation in relationship to the sun. Think of the rounded form of planet Earth, in constant rotation and in curvilinear motion. The artwork presented here considers the sinuous curves of the earthly realm, from the shape of a shadow to the drape of a curtain and the extruded form of a three-dimensional painting.

Shaping Landscape

Brian Autio / Andy Brown / James Cooper / Janice Everett / Heather Bird Harris / Patty Harris / Howard Hastie / Erik Peterson / Candace Knapp

If shape is just an interplay between light and shadow, there is no better place to consider the shape of things than where the sun shines most brightly. Artists here consider how shape can be a device for reimagining landscape, but also how physical terrain carries its own essential form. Landscapes both natural and domestic are all rife for artistic exploration.

Body As Form

Melanie Brewster / Daria Denisenko / Pamela Merory Dernham / Sami Mordecai Elderazi / Marcel Ceuppens / Goran Konjevod / Ron Chereskin / Samuel Schwindt / Mark Wieder

Bodies come in all shapes and sizes, or so the saying goes. As young artists, we first learn to render the human form as a series of interrelated shapes: a circle for the head and lines for the torso, legs, and arms. Artists for time immemorial have captured this fascination with bodies, even considering the shapely proportions of the human form, as in Da Vinci’s Vetruvian man. Whether in motion or in a state of repose, the work presented in this section considers the twisting planes of the human figure as a site for shapely discovery.